The World Cup knockout rounds wrapped up in arguably the greatest final (possibly match full-stop?) we could have asked for. Whether it was Messi getting his crown or Mbappé scoring a hattrick and strengthening his case to be considered the best player on the planet currently , there were tons of narratives! Many of which, of course, don’t tell the full story.

As with the previous article I wrote, which covered the group stage & early matches in the knockout rounds, I’m going to take a look at some of the most interesting matches from this winter’s World Cup, and present & hypothesise (with the benefit of hindsight it must be said) why games went the way they did & how I, if i were to be employed by a team taking part, would suggest potential fixes to change the result in our favour.

Morocco v. Spain

Morocco’s run to the semi-finals was the “feel good” story of the World Cup (in a tournament which badly needed one due to *gestures broadly at everything*), and no match encapsulated the Moroccan style better than the match against Spain in the round of 16. An energetic mid-block that stifled the Spanish possession game and forced them to go the distance. I’ll be looking at this game from the Spanish side of things:

What Problems Morocco Presented The Spanish

Setting up in a 4-1-4-1, Walid Regragui’s team forced Spain to keep possession in non-threatening areas, protecting high value areas of the pitch. Structurally, both the wingers on either side would sit very deep and flat, in line with their central midfielders. By doing so, they helped prevent early passes wide to the Spanish full backs and also stayed compact between lines. In the midfield, the Moroccan #8s/CMs would press out and engage the ball when the CBs had the ball. When this dynamic occurred (as shown below) the other CM would stagger/drop down, thus protecting the #6 positioned deeper and preventing him from having to constantly move laterally to protect between lines. On top of this, the player they had at the #6 position, Soyfan Amrabat, was sensational at cleaning up danger in front of the back four, as well as helping to protect the half space areas of the pitch that Spanish midfielders looked to occupy. Because of all these reasons, Spain were able to keep the ball but not create many dangerous chances in front of goal.

What Spain could have done in possession

Firstly, a common rotation that Spain utilised throughout the tournament is shown below.

It sought to create space in wide areas by disrupting the reference points of opponents. In this match, a better use of this rotation could have helped cause issues for the wide players in Morocco’s system. As mentioned, a key part of the winger’s role was to drop flat & help protect early passes out wide – Through more intelligent use of the FB to pin or fixate the Moroccan winger, Spain could have access these wider areas with more regularity. Instead, Morocco could cover both wide & central areas which led to forced passes & interceptions, or them pulling out possession and recycling.

Secondly, a better use of pass type variations would be something I would highlight as a potential fix. Variety isn’t just the spice of life, sometimes it’s the spice of *checks notes* good attacking play. Spain’s system consistently tried to pick its way through the central areas of the pitch, areas which Morocco had protected previously. Essentially they played into traps. Whilst very good at staying compact & preventing passes through them, Morocco still played with a relatively high line and hedged towards the near side. As shown below, thanks to a wonderful screenshot from István Bergei, if Spain’s winger was encouraged to invert inside when the ball was on the opposite side of play it would draw the attention of Morocco’s winger & create spaces for switches of play for the full back free to receive.

Finally, tying into the theme of pass variations, Morocco’s shape, as touched on above, was compact both horizontally (i.e. between the lines), as well as vertically. This meant there was decent enough space to warrant looking to try and slip passes in behind. To do so, Spain would have needed very little in terms of structural changes to create these dynamics. The rotation they looked to consistently create throughout the match (full back inverts between the lines, midfielder pulls out into vacated position) would enable a lot of slipped passes beyond Morocco’s defence. The full back should position himself right near his opposite player whilst the winger stays high and wide, allowing him to make movements from out to in. These two players would effectively create 2v1s against the Moroccan full back; one pinning him inside, the other profiting.

England v. France

England played extremely well against France, but such are the margins of knockout football that it proved to not be enough against the eventual finalists. From a tactical perspective, the story of the match largely came in the form of how Mbappé’s threat was counteracted by England – a theme that will be touched on again in the section covering the final. Essentially, Southgate & his team “broke” their entire normal offensive organisation to try and protect against the French forward’s ability in transition when the ball was won.

How England Adapted/Changed

Within England’s 4-3-3, the back four had an asymmetric shape by design. Walker, who was fit to start, was tasked with tucking in very narrow when they had the ball, occupying Mbappé and holding his hand (not literally) as a protective measure. Rather than flexing wide onto the touchline and allowing the forward to profit from the space between Walker and the centre back, by staying narrow Walker and England had ready-made fail-safes (as shown below), putting the full back in position to defend should they lose the ball.

Ahead of the ball, Jordan Henderson would flex wide onto the touchline, staying in the traditional full back positions Walker would normally occupy. While England were broadly fine with this approach, it had a number of downsides for them in terms of chance creation. For one, the personnel. Jordan Henderson is a great player, but “progressive/creative” passer is not really his strong suit. Putting him into the wide areas as an outlet (whilst simplifying the areas he could play into), forced him to try and act as the facilitator for a lot of attacks England put together. Secondly, it pulled out a midfielder from the middle of the pitch consequently forcing Harry Kane to drop deeper, Saka (the winger on that side) to invert inside, etc. As was shown by the course of the game, England were at their most dangerous when they could isolate Saka 1v1 out wide and this dynamic was nullified whenever Henderson pulled wide. So how to bridge the gap between safety-first & chance creation?

How To Solve A Problem Like Mbappé

Trying to stop a generational player like Mbappé? Full disclosure – Not easy! My potential fix still retains the build up structure as before, but looks to create central penetration through the middle rather than out-to-in. France defended in a 4-4-2 with Giroud and Mbappé. As touched on before, Walker was occupying the latter (and the forward isn’t exactly “diligent” shall we say with his off ball work). Despite England having this advantage against the forward line of France, they did very little to pull them apart. England instead built around the sides of the pitch in non-threatening areas with their midfielders pulling wide (as mentioned with Henderson) and France remaining comfortable.

As an analyst, I would look to reinforce to our players that staying high and between lines does more for us than constantly trying to get on the ball wide of France’s shape. With a back four against two (maybe 1 and a half with Mbappé ‘defending’) you already have the numerical advantage to progress the ball. Let the centre backs drive forward into pockets of space and let the dominoes fall. As we will see with the next game I highlight, there are tons of opportunities for midfield trios to dominate a flat midfield four. England were able to do one of two of the most important aspects of build up play – get the ball forward – but not the second – move the opposition around. If you don’t do both of these, teams can stay compact/behind the ball/ etc. and while you might have territorial domination against the defending team, it won’t be qualitative domination. To sum it up – don’t break what isn’t broken, and tell my players to stay disciplined ahead of the ball.

Brazil v. South Korea

In the Round of 16, Brazil met South Korea in a match which was effectively over within the first 30 minutes. Despite getting dumped out of the tournament by penalty specialists Croatia in the quarter finals, and this being a relatively high point for the Brazilians this World Cup, I still maintain they were one of the best teams this winter. Had variance and a bit of luck gone their way, it is very likely that Brazil would be semi-finalists, but that’s by the by. Looking at this game isolated from the Korean perspective, I will present a number of potential fixes for how they could have stayed in the game longer and prevented Brazil’s simple and comprehensive victory.

How Brazil Tore Through The Korean Defensive Set Up

Whilst nominally setting up in a 4-4-2 without the ball throughout the Group Stages, it was only in this match that the inefficiencies that this shape (and by extension, only using two central midfielders) can have against a team who exploits the +1 in midfield well. In their matches against Ghana, Portugal, and Uruguay, the two Korean forwards, Heung Min-Son & Gue-sung Cho worked in tandem well. The ball side forward pressed the opposition centre back, and the other dropped down to cover the pivot position. This clogs up entry passes into the middle third & negates the +1 the opposition have in midfield.

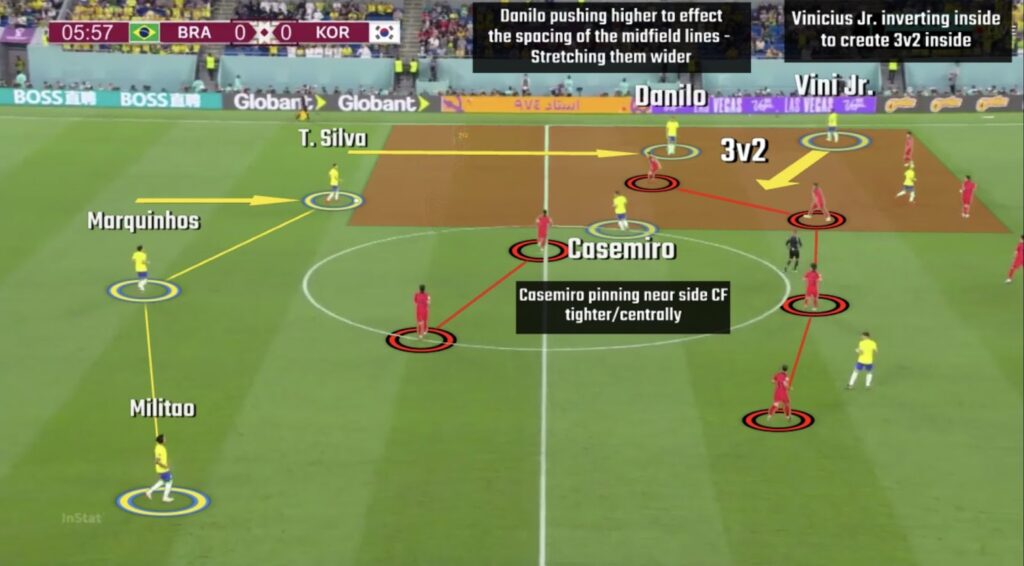

This dynamic upfront for Korea was effective against teams who played with two centre backs, which all their group stage opponents did. Essentially, Korean could go 2v2 in the press and do so with relative comfort at the distances between protecting their midfield and engaging the ball. Brazil, however, while playing in a back four on paper, built up with three at the back. This flipped the build up dynamic in their favour and making a 3v2.

As shown in the graphic & still image below, the near side full back would push high & the winger would invert inside to occupy the half spaces.

On the weak side, the full back would stay deeper and act as an auxiliary centre back. Adding in this extra player at the back allowed the centre backs to spread wider, meaning that Son and Cho had to cover more distance (which they were unable to do) and act in conjunction with one another.

Furthermore, ahead of the ball, the Brazilian players would pin (see the diagram) Korean players away from the ball and allow the likes of Thiago Silva and Marquinhos to make defence splitting/line breaking passes, Within South Korean’s 4-4-2, the midfield lines were flat which exasperated their issues.

How Korea Could Have Fixed It

It’s easy to say when you are watching from afar, but as soon as I noticed that Brazil would be building up in a three (if I had not seen this when watching them earlier in the tournament) I would have suggested a simple change in shape. Drop one of the two forwards (most likely Son) deeper from the start, and set up in more of a 4-2-3-1 shape. Keeping the two forwards high and detached from the midfield exposed them, and allowed Brazil’s rotations to be at their most effective.

Rather than trying to engage the centre backs directly, screen the entry passes into the midfield and cut off the options, rather than the supply. While reactive on the surface, Korea’s gameplan anyways was one set up to win possession and counter quickly. Croatia for example did this quite well. By setting a lower and more compact line of confrontation, they forced the Brazilian forwards that were ahead of the ball to pull out into non-threatening areas rather than receive on the half turn through them. Even more so, Croatia’s midfield was….old, there’s no other way to put it. The same triggers but with the energy that Korea had would likely have proved a better deterrent.

The Final – Argentina v. France

The first 70 minutes of the match were a story of complete domination by Argentina with France barely in the game. However, much of the interesting tactical elements of the game were caveated by France’s pre-match issues in regards to player fitness/energy levels (we’ll just call them “stomach discomfort” to spare any of the details). I do think that what Argentina were able to do with these obvious caveats is worth mentioning though!

How Argentina Attacked – And Nullified France

Argentina’s manager Lionel Scaloni made a number of tweaks throughout the tournament, both in terms of personnel & team formation/shapes. For the final, he selected a traditional 4-3-3 with a front three of Messi on the right, Julian Alvarez as the #9, and Di Maria on the left. Di Maria’s selection was the vital choice which enabled Argentina to hold a seemingly comfortable (funny saying that now) 2-0 lead for much of the match.

Di Maria was played as a a winger who stayed as wide as possible on the touchline, rather than inverting inside as he tends to do on the right. By design, the winger would always “cheat” wide when Argentina were in possession, acting as an outlet for the team. France, understandably, wanted to prevent and protect their opponents from playing through Messi on the other side of the pitch, overloading and trying to force play away from their star player. While Argentina would obviously look to try and use Messi at every opportunity, the combination of France overloading the right (if we are looking at it from Argentina’s perspective), and Di Maria being free high and wide on the left was the main way the South American side created threat in the first three-quarters of the game. Starting right & finishing left. Overload, isolate, to final third. A classic of the genre.

While obviously stretching and creating issues for their leggy/tired defence, it had an effect on how France wanted to attack Argentina for these periods of the game. With most of the play coming down on one side of the pitch, it made it incredibly difficult for Didier Deschamp’s team to create transitions through Mbappé. Rather than having an immediate outlet on the near side, France had to switch play to the other side, and do so with an extra 15+ yards to cover. Quite ironically, the way Di Maria stayed high and wide *in* possession was how Mbappé positioned himself *out* of possession when France had the ball. Making these starting positions more difficult for the pacey forward consistently allowed Argentina to keep the ball. As mentioned at the start, the entire context of the game was shaped by France and their issues with fitness and this must be noted. Ultimately, who knows if the use of Di Maria would’ve been less effective had their opponents been able to assert themselves more.

The Chaos That Ensued

After France scored their first goal and then quickly equalised, the entire match became a chaotic mess. There’s no other way to put it. Of course, every analyst worth their salt likes to think they could be the one to change the course of the game towards their favour. However, rather than try and pontificate that way, and present what I personally think could have happened for either side I’m going to put it bluntly: it’s a World Cup final, the most emotionally charged match you can think of. The game was end to end, with zero control throughout the latter stages. This highlights to the umpteenth degree something that is and always should be true of any analyst’s workflow – football is about the players.

How did Argentina get their penalty? An individual mistake. How did Mbappé get his first penalty? Once again, an individual mistake. Sometimes players pull rabbits out of the hat and sometimes they mess up. The World Cup encapsulated everything about this perfectly. I could tell you that Argentina needed to manage the end of the game better prior to France exploding, but up to that point they faced zero shots. I could also tell you that France needed to be more conservative prior to Messi scoring the third goal, but the game was stretched beyond recognition. As an analyst you need to contextualise all the information you provide (such as what I did with France’s illness pre-match), and being realistic with what sort of feedback you can provide certainly falls under that category.

Conclusion

Aside from the fact that it is always fun to try and decipher what coaches are trying to do, there is one main take away that I would like to highlight.

In providing the pictures of these games, I have done so with two things in mind: the context of the scenarios that matches presented, as well as what was actually possible, a.k.a. actionable insights.

In regards to context, there are plenty of different scenarios and factors that go into analysis on the fly or when working for a club. You must know the game model and how you want to play, you must know the personnel at your disposal, how your suggested changes will affect the opposition, etc. These are just a few examples. If you don’t use this context in your work, it will be unusable. You can’t tell a team that doesn’t like to press that they should suddenly start doing so 15 minutes into a game.

For actionable insights, this is the biggest area which separates real work that is done at the professional level and that which is done on social media/publicly. Ultimately, what is important as an analyst? How much you can affect change. Because of this, you need to ensure your information can be used on the pitch where it matters most. That means (using the aforementioned contextualisation) it needs to be concise as well as presented in a manner which doesn’t require much explanation. I hope I have done that for you in these short pieces I’ve written.